I woke up at about 08:08. For some reason, I had looked up the five towns of Prague: the Old Town, the Lesser Town, the New Town, the Prague Castle District and the Jewish Quarter. The weather at 10:35 was 22° C, which was the high for the day. There was rain in the forecast; it was partly cloudy.

By 10:57, I was downstairs eating breakfast. I had gotten a chocolate muffin and two pain au chocolats. I also had an iced tea, Pfanner Pfirsich flavour, otherwise known as peach.

I navigated some routes to see while eating. At 11:24 it was 71° F. I did some research on Alfonse Mucha, since there was a museum there in his name. By 11:52, I was outside. It was still 22 degrees Celsius out.

I knew I was supposed to be headed towards the Žižkov Television Tower. According to Google, the cost was $12.77 to enter. My walk there led me through a part of town that I had not seen before. It was a very leafy area. Because it was around 12:00, I heard church bells ringing. I stopped to film a video.

The houses were odd and unusual; they were unfamiliar, but impressive. They had towers as well. I had never seen anything like it before. They also had various colours.

I hadn’t really seen people walking through this part of town, however, it was a very nice area. It was definitely not a tourist area. There were so many leaves on the ground and I was enjoying it; it was really beautiful to see. The most impressive part of the walk really was the homes, along with the leaves; at least for this section.

I did end up seeing a bust of a man named František Křižík, which was incorrectly dated from 1850 to 1941. He was a Czech inventor who was compared to the likes of Thomas Edison in his day. He introduced electricity to Bohemia and Austria-Hungary.

Eventually, I reached a very architecturally different looking church, something like I’ve never seen before. The name of the church is “The Church of the Most Sacred Heart of our Lord” (Kostel Nejsvětějšího Srdce Páně, in Czech).

After wrapping around that, I could see the tower. It was definitely what I was expecting to see. This part of Prague was very visually interesting. There were three different styles of architecture going on in my view; one was classic, one was modern, one was brutalistic.

There was also some kind of odd installation in front of the church, however I did not spend much time in this area. There were a lot of seated people.

The sculpture in front of it (surprise, surprise) was built by a guy named František. It’s titled “Christ on the Cross” (náměstí Jiřího z Poděbrad, in Czech)

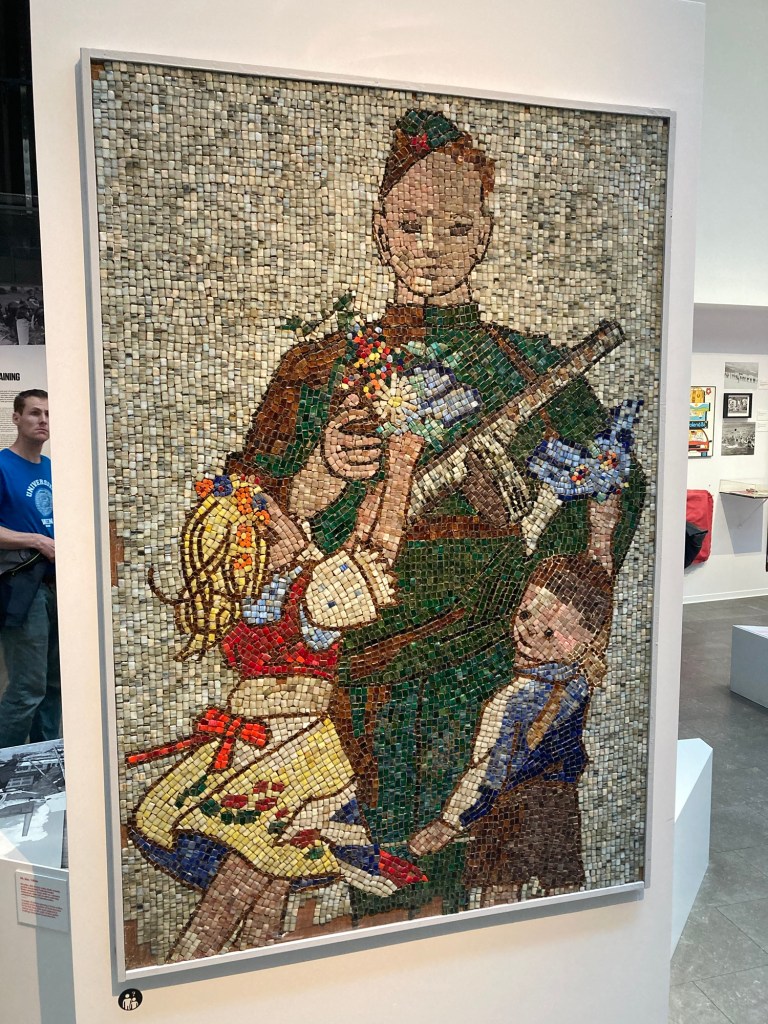

There were small Soviet sculptures etched into the façades of buildings I came across. Many were of workers. I had seen this style before, but only in images; Soviet bas-reliefs. At that time, they were meant to symbolise Soviet progress in society. They typically depicted industrial labour and agricultural work. This style is referred to as “socialist realism”, which was the officially sanctioned style of art in the Soviet Union and other socialist republics, from the 1930s until the end of the 1980s (which is nearly the full length of the Communist regime in Europe).

It was absurd to me to see a Soviet statue on a brown and grey building (in the 21st century).

Eventually, I came to see the tower, which was covered in babies; big, black, faceless, fiberglass babies ‘crawling’ up and down the front side of the tower, the side that I was facing. I could count eight from where I had been standing. There are ten in total.

I stopped and basked at how generally ugly the structure was. It is probably one of the ugliest buildings I’ve ever seen, outside of the City Hall in Toronto, Canada. This was pure Communist architecture. This was like the TV tower in Berlin, but much worse. It was like it was built to be distracting.

I stopped to read about some of the TV towers and transmitters in Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic. This one in Prague is the tallest building in the city, standing at 216 metres. The architect developed 20 different designs for the transmitter. “A futuristic version of the subtle yet stable three-column structure, which resembles a rocket taking off, was chosen”. Construction began in 1985.

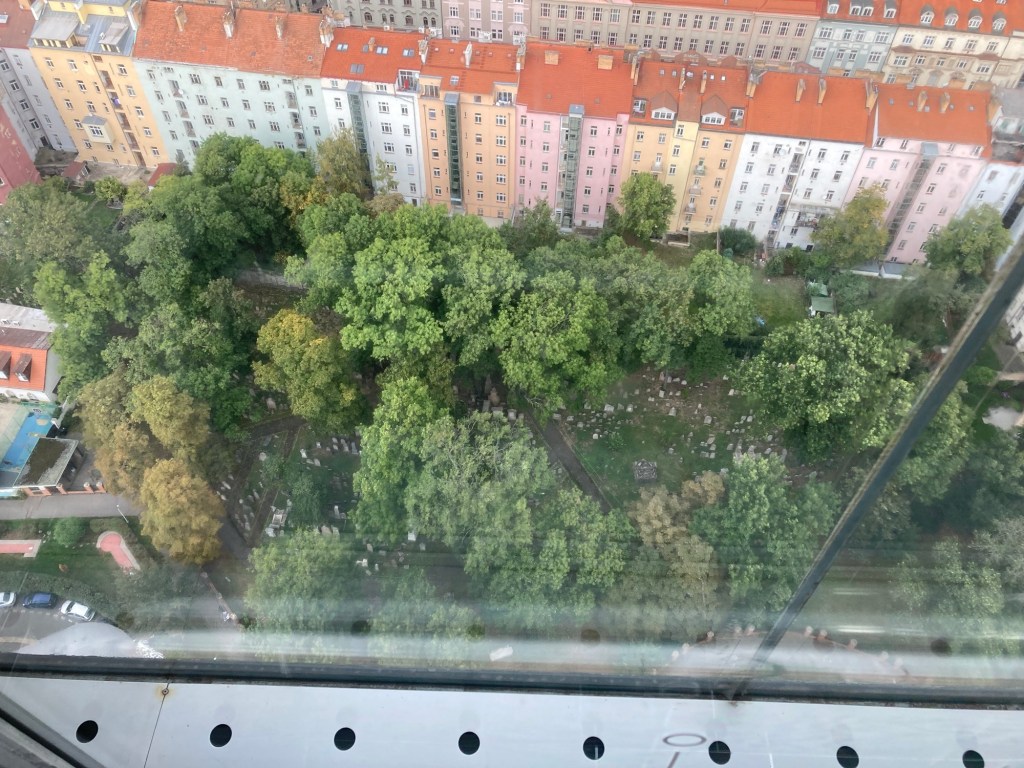

Behind where I was standing was an old Jewish cemetery.

As I got closer to the tower, I could see how dystopian it truly looked; it looked abysmal. This was the Prague I was unused to; however, I wanted to see (I was interested). Around 12:30, I went in. I spoke to the man at the ticket counter, then I sat down and purchased a ticket online. The ticket was 300 crowns.

Ten minutes later, I was up top; the fourth floor. I was able to see a model of the tower, which was hideous as well (only because of its resemblance to the tower). I never want to see this kind of architecture in my city. However, the views up top were not hideous; they were anything but hideous. From here, one could see the whole town.

There was even a display of how it appeared at night. From the bottom, it was lit blue then red and white above, in that order. These colours represent the colours of the Czech flag.

I could see storm clouds heading in from one side of the tower.

I was able to see some block housing, which was noticeable because of the contrast between them and the regular housing. The regular housing had red roofs, while the block housing was just grey and white (with maybe some black mixed in); it stuck out from the city below.

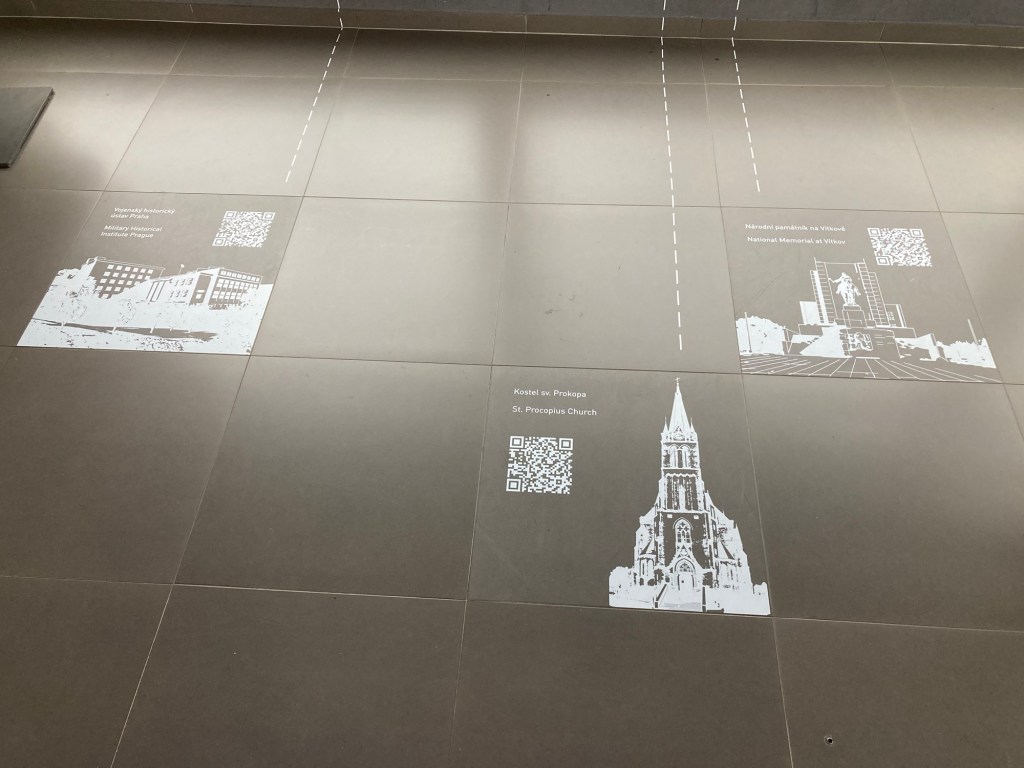

There were certain viewpoints marked on the ground, to identify certain sites or structures in the city. For example, I was able to see St. Procopius Church, which was outside and below, because the area I was supposed to look at had been marked on the ground. These labels extended to circled points on the windows, and I was able to see the location that had been marked. Granted, I did have to bend down a bit.

Just behind the church, and about halfway through a park, the National Memorial at Vítkov stood. An important battle was fought on the hill (Vítkov Hill) in 1420, nearly one year after the First Defenestration of Prague. The memorial was completed in 1938 as a symbol of Czech resistance, months before the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia began. It was later used as a mausoleum for Czech communist leaders.

From above, I could see many of the graves featured in the Jewish cemetery I had mentioned before. It’s aptly called “the Old Jewish Cemetery in Žižkov”, and was established as an emergency burial site in 1680 following an epidemic of the bubonic plague. It was in use for two-hundred and ten years and is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Prague today.

During the construction of Žižkov Television Tower, excavations of the land resulted in grave remains being hit. Bodies were exhumed and relocated by authorities, which disturbed the Jewish community in the area. This is still a controversial part of Prague’s city history today.

At one point, I could see the Powder Tower and Church of Our Lady before Týn, the most of it I’d seen at this point.

The views from above really lets you see how densely packed Prague is.

By this point, visibility had dropped due to the weather. I could see a square of housing which I really enjoyed looking at. I could see the church I had passed by on my walk to the tower as well.

I could see a few skyscrapers as well, located in the Pankrác district.

At some point, I could see the National Museum and the Church of Ludmila, which was nearby to where I was staying, but then it began to rain. I could actually see the rain being carried in by the clouds before this. My photos from this point on weren’t excellent, but I tried to make do with the rain.

What was most important to me was seeing the historical centre of Prague and the Charles Bridge.

At some point during the walk, there was information about the tower and its construction listed on the wall. It did at least acknowledge the fact that graves were exhumed and built over, however, it claims that this happened under the supervision of representatives from the Jewish community.

There was a part of the last observation area, of which there were three, that had a coin binocular on the floor. I did not pay to use it, as I thought my eyes were good enough. Plus, I wouldn’t have had coins. I think I had mostly spotted all the different landmarks that were listed on the floor, if not all of them.

Before I left, I set up my phone on a designated “selfie point“ that was set there for the purpose of taking self-portraits. I took one.

I then eventually mustered up the courage to ask someone standing nearby if they would take a photo of me. They agreed to.

I took one last look down the rain-marked windows, took some photos of some people sitting in bubble chairs, then I left. I was the only person in the elevator (or lift).

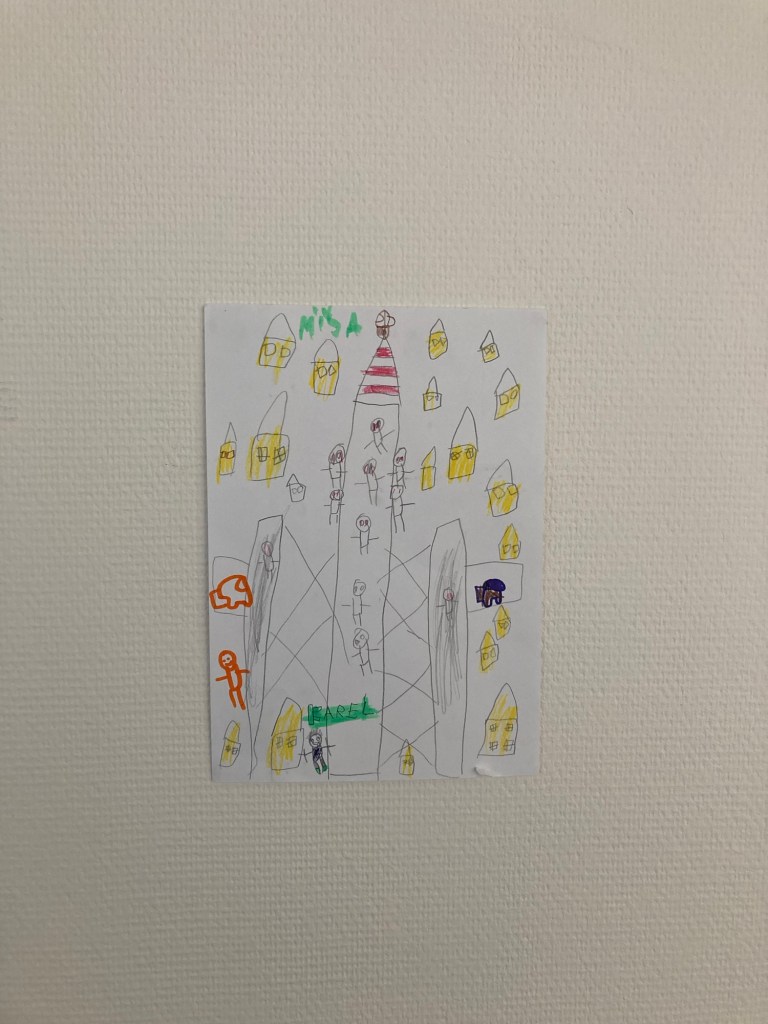

Before leaving, I asked the man who initially told me how to get my ticket where the water closet was. He directed me, and it was only a short walk away. During the walk, I stumbled upon a child’s interpretation of the tower.

It was quite accurate.

I then walked outside to see the thing in person; scary.

With it being 13:44, and having spent an hour inside, I decided to walk to the Museum of Communism. It was a 26 minute walk; 1.3 miles (2.09 km).

I checked out the Jewish cemetery before I left. It was not as packed as the one I had seen in the Jewish Quarter the day before. But still, admittedly, densely packed.

I just took one last gander at the ugliness of the tower before I left. It had incredible views from the top, from inside, but it’s just ugly. There’s even a cluster of antennas and satellite dishes, right above the tower’s windowless cabins, that resembles the wart-covered cap of a toxic wild mushroom.

The whole thing really is just odd and anti-human, in my opinion, but I enjoyed it.

At this point, I did pass by some interesting things, however, I kept my phone tucked away to prevent it from being covered by the rain.

Approaching the museum, I could see the Powder Gate Tower, which was very close the museum. Just outside of the historic part, I suppose.

I passed by a neat-looking train station, Praha masarykovo nádraží.

Walking towards the entrance of the museum, I could see a tower of the Týn Church, one of the most beautiful churches I have ever seen.

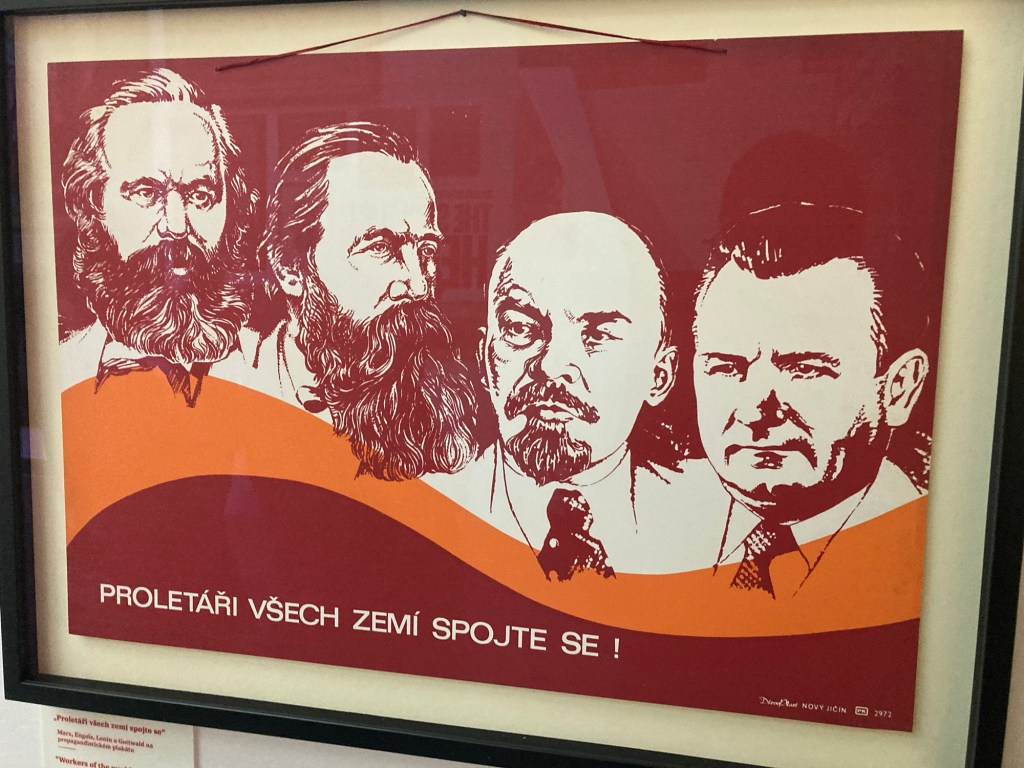

I purchased my ticket and walking up to the entrance of the actual exhibition, I was greeted by a giant five-pointed red star. After that, I was greeted by no other than Karl Marx himself.

He seemed to be short in stature.

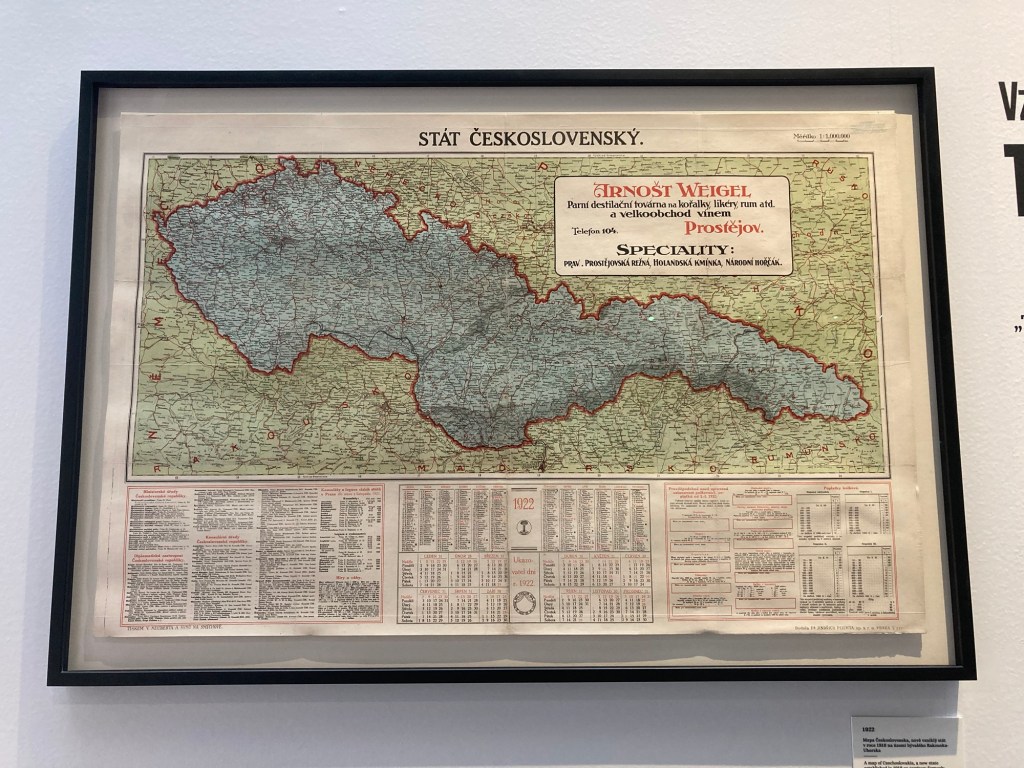

The museum opened with “The Birth of Czechoslovakia”.

There is so much to include about what I saw and read. Larger ideas are boldened, some separated, and one can do research as they will; there are plenty of books and historical documents about this. If one is genuinely interested in this, I strongly implore you to look into this yourself rather than rely on me for details. I can only tell you so much, as I wasn’t there.

For those who would like to conduct thorough research on things not mentioned here (which is quite a bit), I would recommend Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed by Mary Heimann. Although I haven’t read it, it’s hailed as one of the most well-researched and objective books when it comes to the history of Czechoslovakia. I may give it a read one day.

I AM NOT AN EXPERT, JUST A CURIOUS TRAVELLER.

Let’s begin.

Czechoslovakia was founded in 1918 with the help of US president Woodrow Wilson and was given remnants of the Austria-Hungary empire. The Communist party of Czechoslovakia was founded two years later.

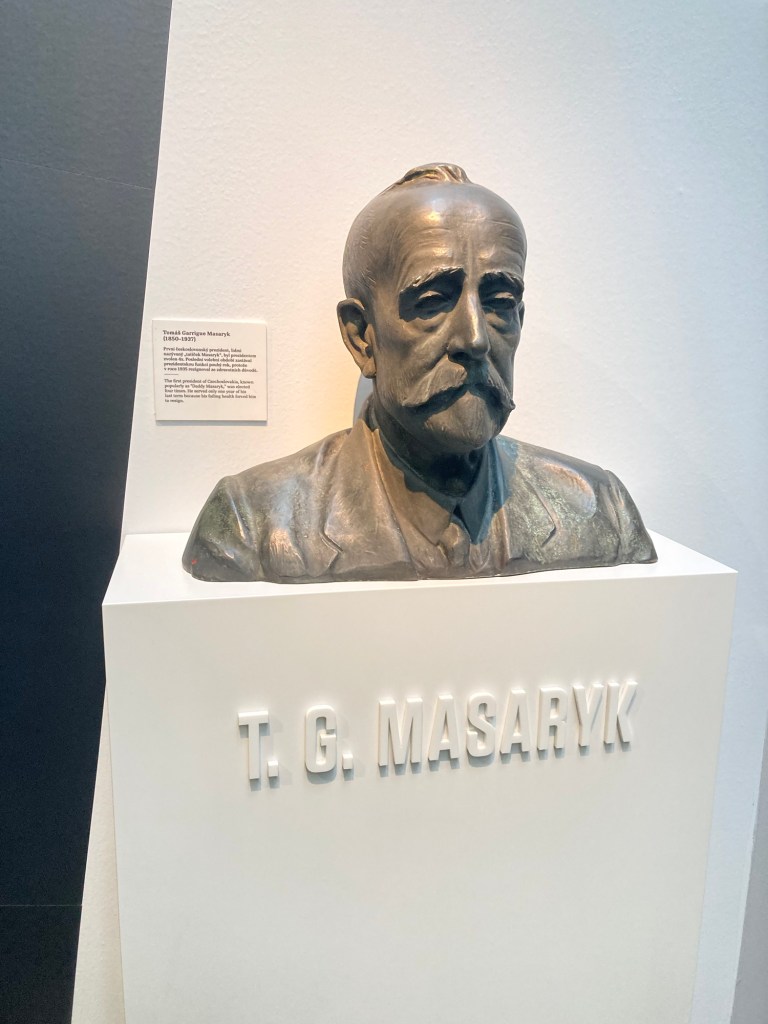

The train station I had walked by on the way to the museum was actually named after the four-time elected founding father of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

The actual fathers of communism itself were Karl Marx and Frederich Engels. They published the Communist Manifesto in 1848. The poor working conditions of the late 1800s (the industrial era) really set their ground work into motion.

There was a quote on the museum wall saying, “according to conservative estimates, Communist experiments of putting Marxist theories into practice resulted in the deaths of up to 100 million people in the world.”

The Great Depression helped the Communist regime even more. And nationalists. And fascists.

When Adolf Hitler became the Chancellor of Germany, Czechoslovakia strengthened its fortifications on the border. They were essentially rendered useless by the Munich Agreement of 1938, which transferred Czechoslovakia into Hitler’s hands without any kind of large fight. Large portions of Czechoslovakia were handed over to Germany, with approval from France, Italy, and Great Britain (notice how I did not mention Czechoslovakia, because there was no Czechoslovakian representation whatsoever).

Czechoslovakia gave up its region with the largest ethnic German population, the Sedentland. The area accounted for about 30% of the country and contained around 10% of its population when the land was ceded to a devastating power.

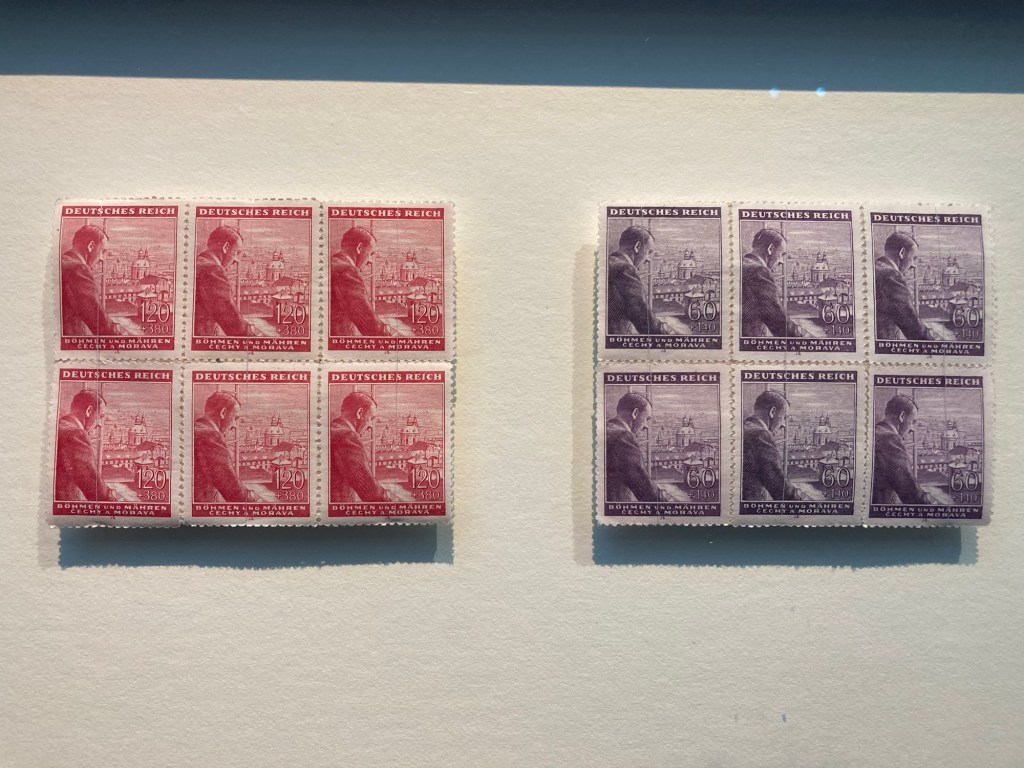

The Czech region fell and was eventually occupied by the German army until 1945. The sitting president of Czechoslovakia at the time, and the leader of the Communist party went into exile.

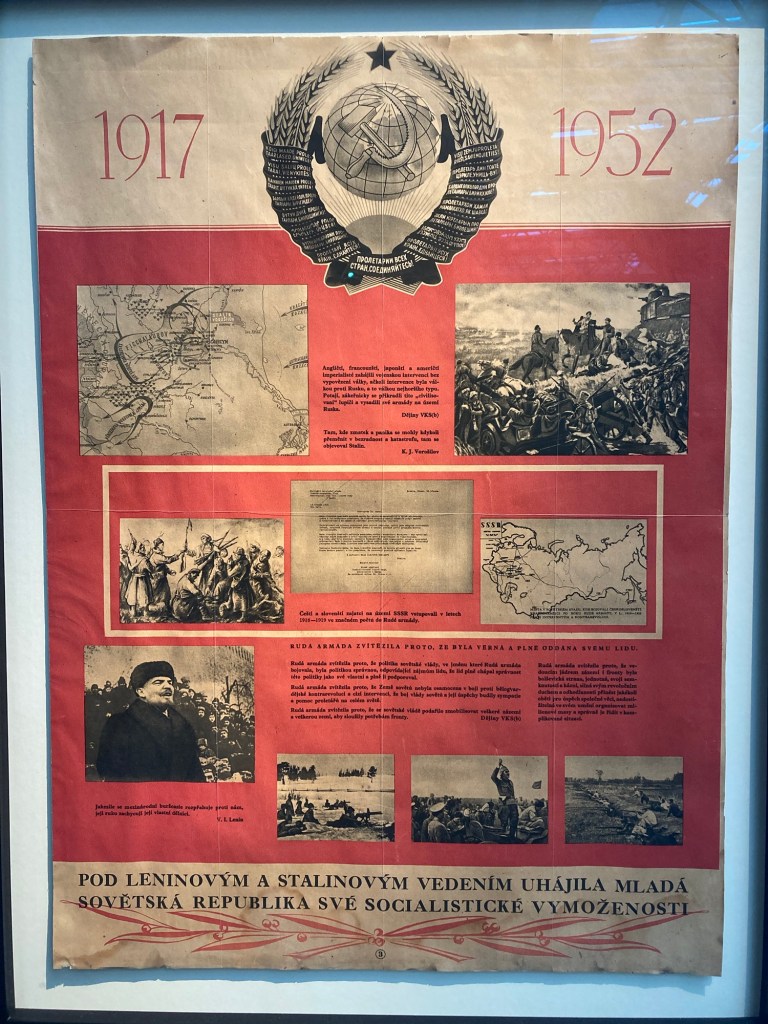

The Liberation of Prague by the Red Army

Public executions were held for those found guilty of war crimes. Events like the formation of the Central Intelligence Agency in the USA, and the Marshall Plan, gave communists reason to be suspicious of the West, and legitimised the gradual elimination of the private business sector, and nationalisation of industry.

In their heads, the Cold War had begun, and competition between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics began. It was fierce. German scientists were captured and employed on both sides.

There was a general desire in Czechoslovakia to follow the ways of the Soviet Union; it was the model, if you will.

There once stood in Prague a Monument to Stalin (originally named “A Monument to Love and Friendship”) which people were not fond of. The artist behind the statue, Okatar Švec, comitted suicide weeks before the revealing, along with his wife, who comitted suicide in the same way a year earlier. The statue was eventually demolished, following the fate of its creator.

There was some Soviet art hanging.

There was a quote attributed to Winston Churchill saying, “If you put the Communists in charge of the Sahara Desert, there will be a shortage of sand in five years.” However, the quote is more accurately attributed to famous economist Milton Friedman.

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON).

The Czech made backcronyms about COMECON. “Víte, co znamená zkratka RVHP? Radujme se, veselme se, hovno máme, podělme se”. Translation: “Do you know what the abbreviation COMECON means? Let’s rejoice, let’s be merry, we have shit, let’s share”.

From here on, the stories of communism will be less linear, and more so some general ideas mixed with truths.

- Soviet satellite states (also called the Eastern Bloc)

- The new socialist man (or new Soviet man) who owned about the same things as his fellow citizens, and valued working above all

- The erasure of character

- Churches emptied and factories and collective farms filled

- Russian miner Alexei Stakhanov (the most interesting story to me), who reportedly mined 102 tons of coal in 5 hours and 45 minutes, became the face of the Stakhanovite movement for his exceptional work. He mined 14 times the expected amount. This story is actually true, but the circumstances surrounding his feat remain controversial

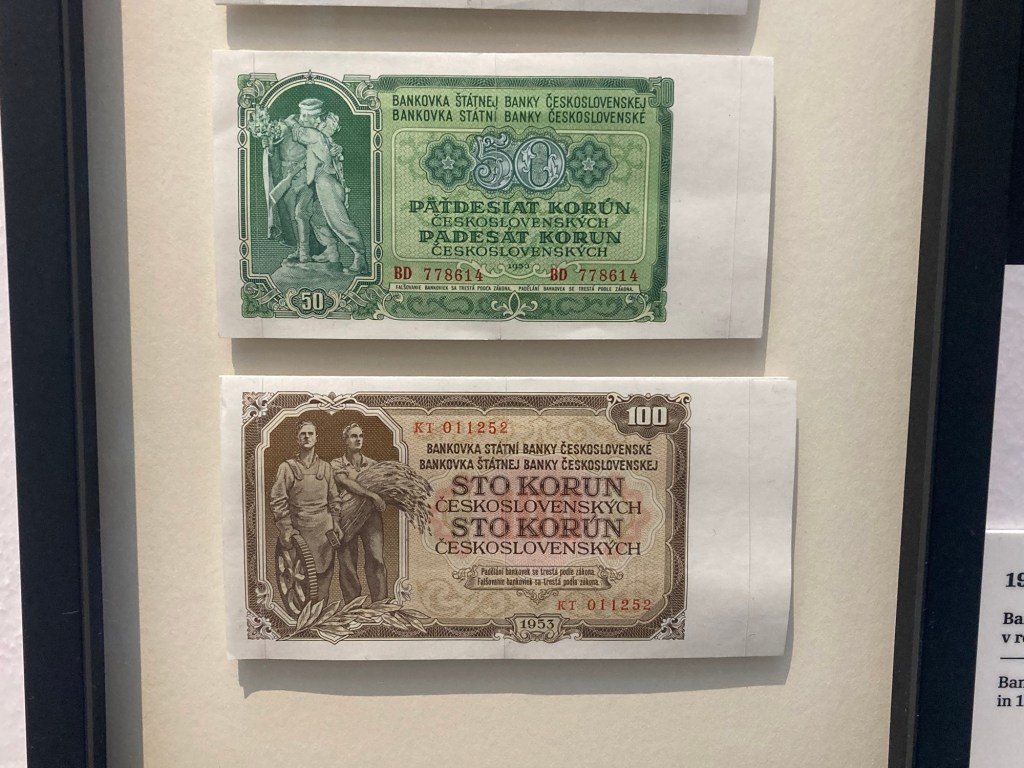

Currency reform of the Czechoslovak Koruna in 1953 meant the value was to no longer be attached to the US dollar via the international monetary fund, and instead it would be attached to the Russian Ruble. Failing state state enterprises were cleared of their debts, but private citizens were left ravished. Cash lost about 80% of its value overnight. According to the museum, money deposited in banks lost 43%.

- Collectivisation – The forfeiting of privately held land by farmers.

- Kolkhozes (collective farms) and sovkhozes (Soviet [state] farms).

“Prosperous farmers were labeled kulaks and were sent to forced-labor camps known as gulags. Several million people died in the Soviet Union as a direct result of the famine caused by disruption in the farming sector and systematic repression”.

Farmers were put up in kangaroo court trials and forced to join collective farms, known as United Agricultural Cooperatives (ZDs). Their properties were seized, and they received nothing.

There was a photo description saying, “in the name of gender equality, socialism offered ‘men’s’ work to women (without alleviating them of household responsibilities).”

- The five-year plan

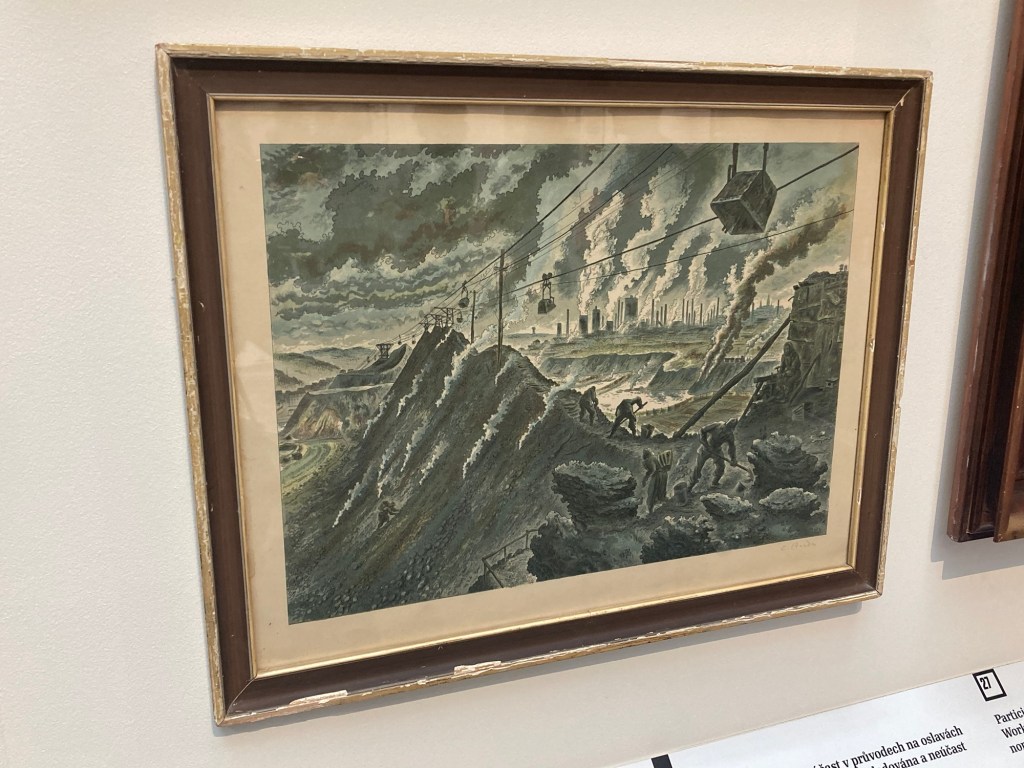

Stalin wanted Soviet society to revolve around the ideology of advancement, and he saw intense industrialisation as the means to do this.There were centrally planned economies, raw material shortages, and high energy demands.

In the Slovakian town of Sered, preschool-aged children were exposed to toxic slagheap (from nickel) that covered an area of 30 hectares. Those young children suffered from severe eye and ear infections, while also possibly breathing contaminated dust, eating food grown in contaminated soil, and playing in polluted areas.

Once Communists realised how behind the rest of the world they were, and that their development ideas weren’t working, they agreed to shut down more than half of the plants.

Unrealistic standards meant energy and material needs couldn’t be met. The environment suffered as a result of these outcomes and efforts, as well as human health. Parts of Northern Bohemia resembled the moon surface due to coal mining. Forests in the region were stripped of nutrients and protective layers due to the acidic nature of the rain that the power plants created. Chemical fertilisers and heavy machinery meant to speed up agricultural production only put a damper on soil and groundwater.

The public was unaware of the state of the environment until the 1970s.

- Propaganda and political correctness

- Distortion of history

- Colorado potato beetle

- The Spartakiad

- Brutalism

- Housing shortages

- Unified construction enterprise

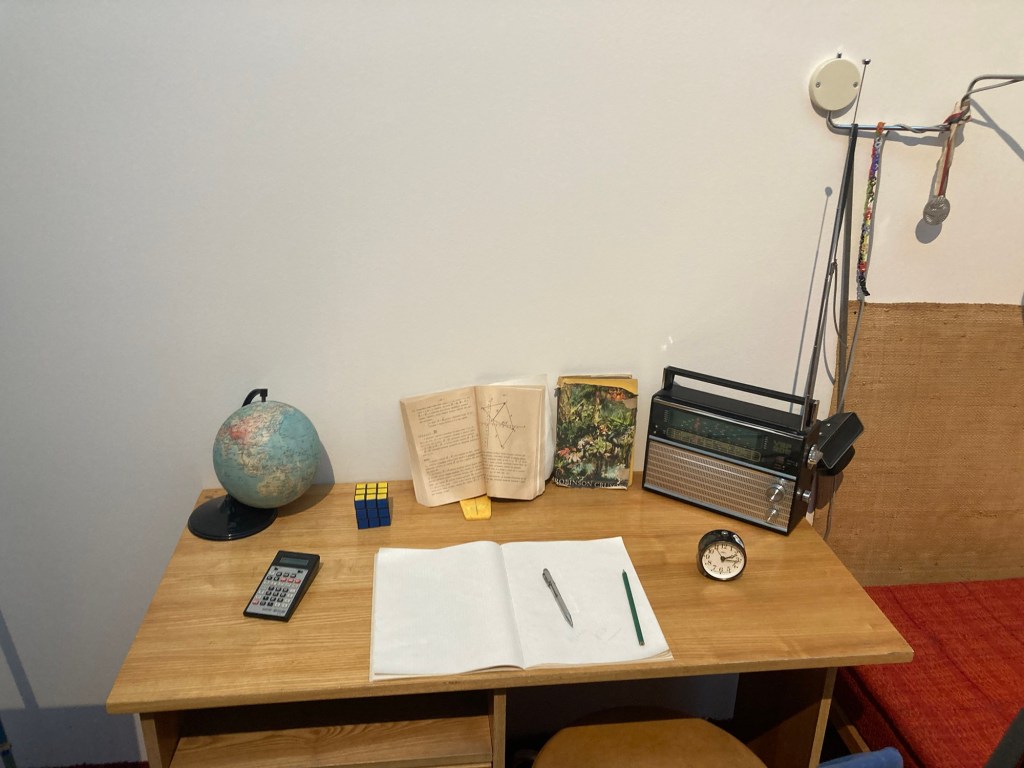

- Tower blocks/block housing

- Uniformity, the absence of privacy, and a true concrete jungle

- Another name for block housing was “rabbit hutches”

I got to take a step inside one of these block tower rooms.

- State-mandated doping system introduced in the seventies

- Artificially provoked acts/riots

- Sanopz state hospital intended only for high-ranking Communist officials and their family members

- Corruption and clientelism in the Czechoslovakian healthcare system

After the fall of communism in Czechoslovakia, the average lifespan quickly increased by about five years.

- The grey economy – The private sector was erased, and it became harder to run a business under the state

People rarely left the country due to restrictions, and if they did, it was only to countries controlled by Russia. For the ones who did leave, they could only bring a certain sum of money with them, and sometimes goods were smuggled back in.

- Bureaucracy was placed above supply and demand

- Tradesmen (those with skills) were in high demand

- Tuzex crowns black market

- The Proud Princess

- Annihilation of free artistic expression

- Elimination of private publishing houses

- Compulsory participation in May Day parades for school children, students, factory workers, and others

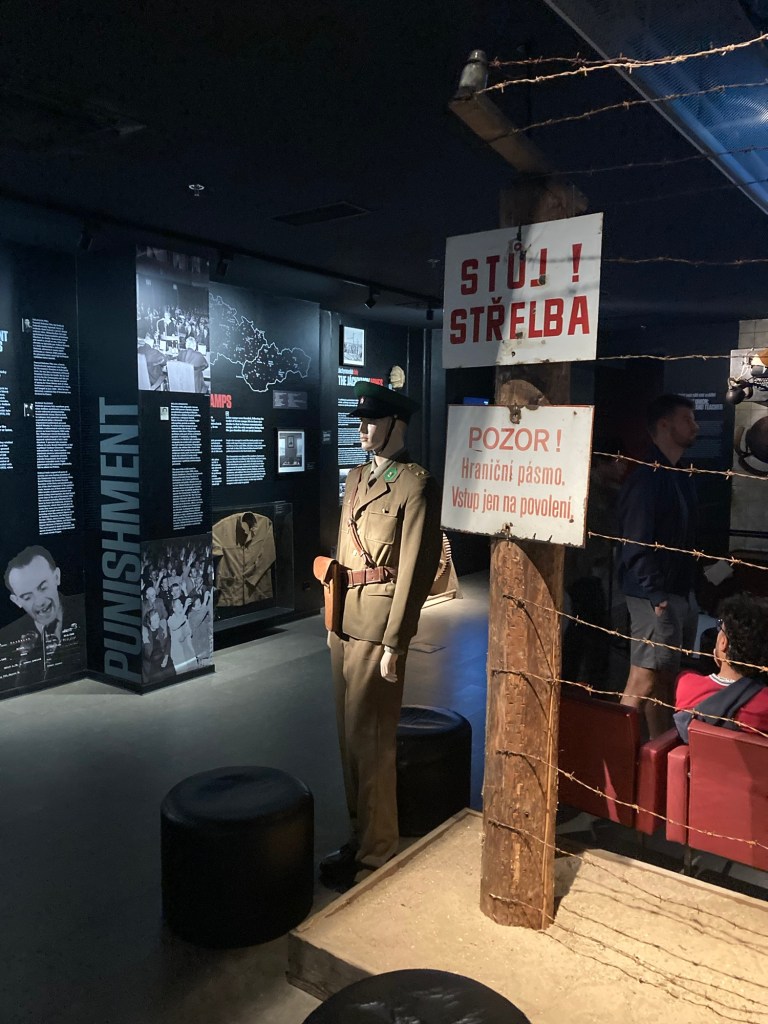

The police were renamed the national security corps with public security and secret state security.

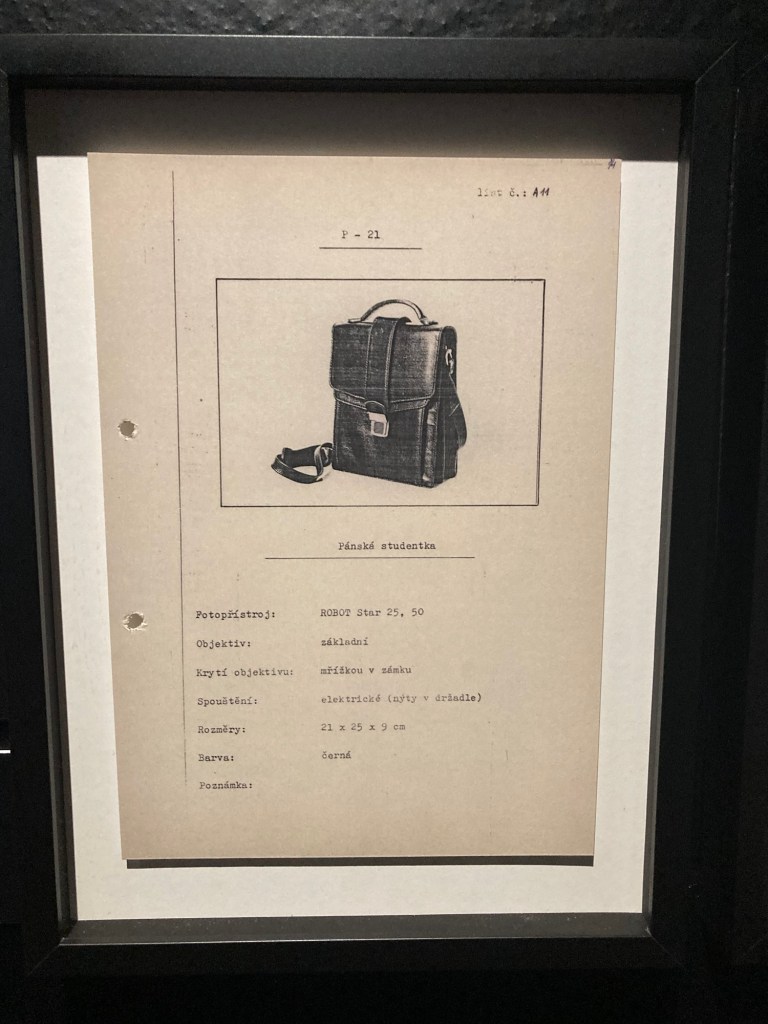

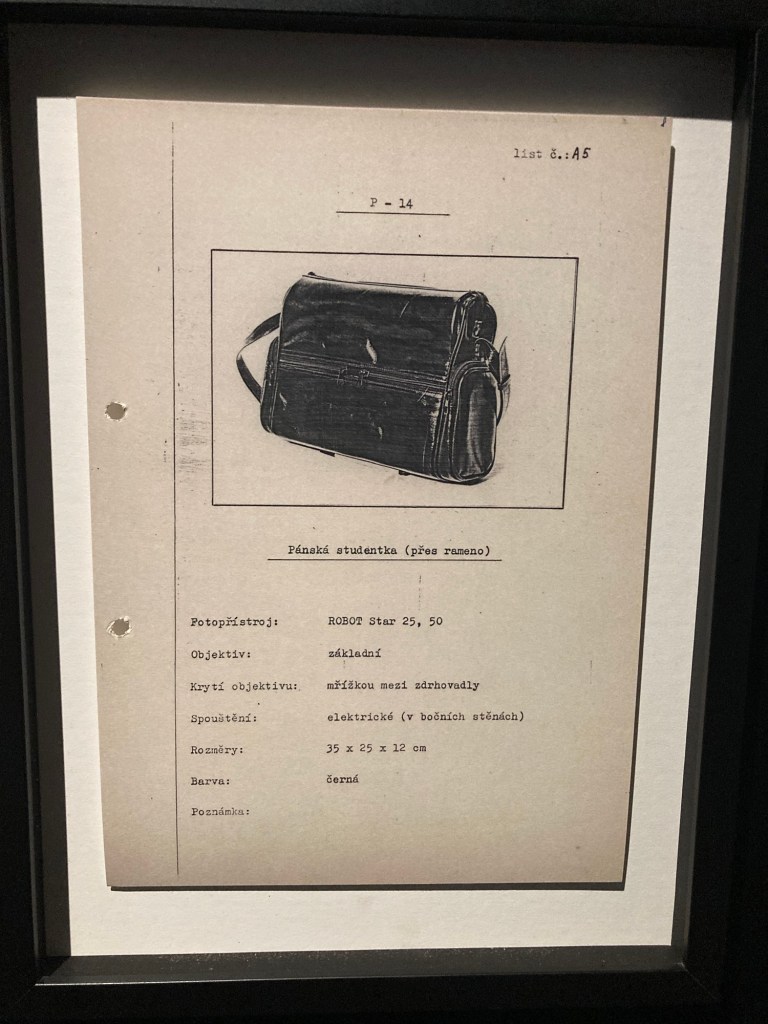

There was a repression of civil and human rights, and surveillance was weaponised against citizens. Harassment was used to silence the opposition of the regime.

Fear was used to manipulate the people.

- Warsaw Pact

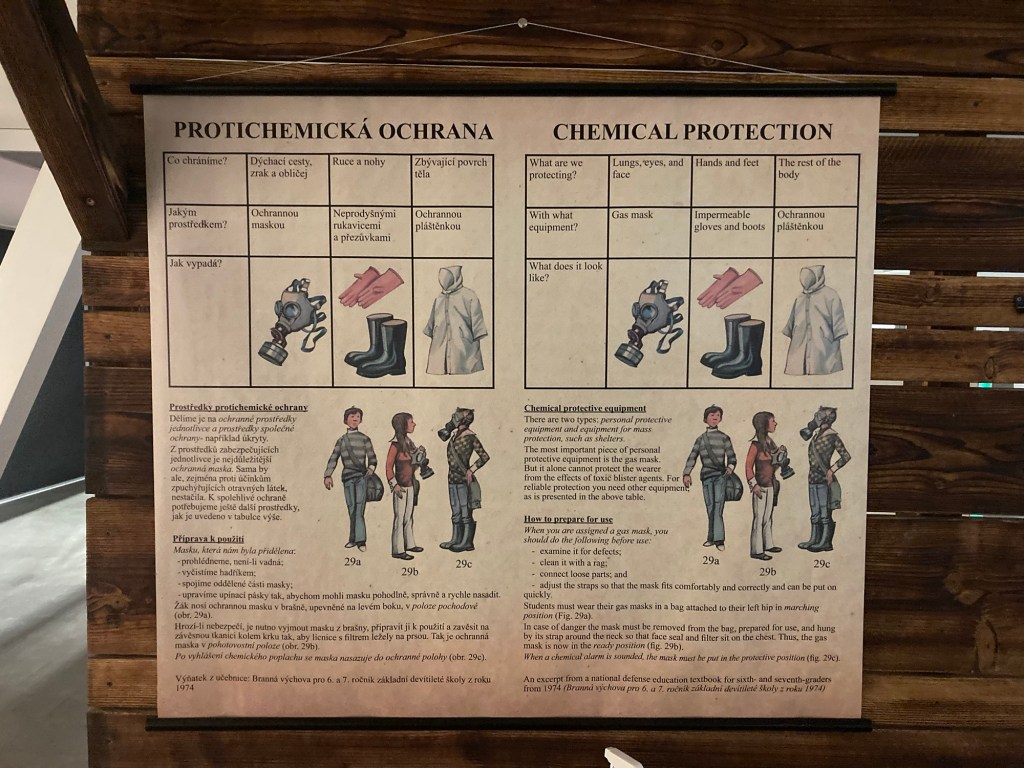

- Civil defence training

- The eradication of voluntary organisations

- People’s militias organised under the direct control of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (which fundamentally doesn’t make sense, seeing as militias are meant to be formed as a civil response)

- Mutually assured destruction (MAD)

- The Cold War

- NATO

- Arms race

- Emigration due to political disapproval

- Civilian informants

- Operation Neptune

The government went to great lengths to discredit people. Athletes, artists, clergy, and former politicians were all put on trial. Torture was implemented to admit guilt. There was no such a thing as innocent until proven guilty.

Capital punishment was centralised. Czechoslovakia had the highest execution rate in the Eastern Bloc (not the USSR, just to clarify). Interestingly, only one woman was executed due to a political trial.

Organised religion was dismantled by the Communist Party. Today, the Czech Republic is one of the least religious countries in the world.

- The Iron Curtain

Labour camps for prisoners were similar to German concentration camps, with the exception of gas not being used to determine outcomes.

Uranium was mined by prisoners without the use of masks.

“Auxiliary Technical Battalions were politically unreliable individuals, who did not agree with the Communist regime… Battalion members included the sons of businessmen and prosperous farmers, politicians from non-Communist parties, people persecuted after February 1948, students expelled from university, priests, and pastors, as well as criminals, the illiterate, and Roma”.

- Brutal interrogation methods, as well as interrogation competitions.

Coming from a working-class family increased one’s chances of making a living, or receiving higher education. Anyone who criticised the regime was persecuted, as well as their families.

- Cadre screening

- Political assessment

Russian was a compulsory subject in schools.

Československa (The Communist Party of

Czechoslovakia) KSČ

- Censorship abolished in the 60s

- Five-day workweek introduced in 1968

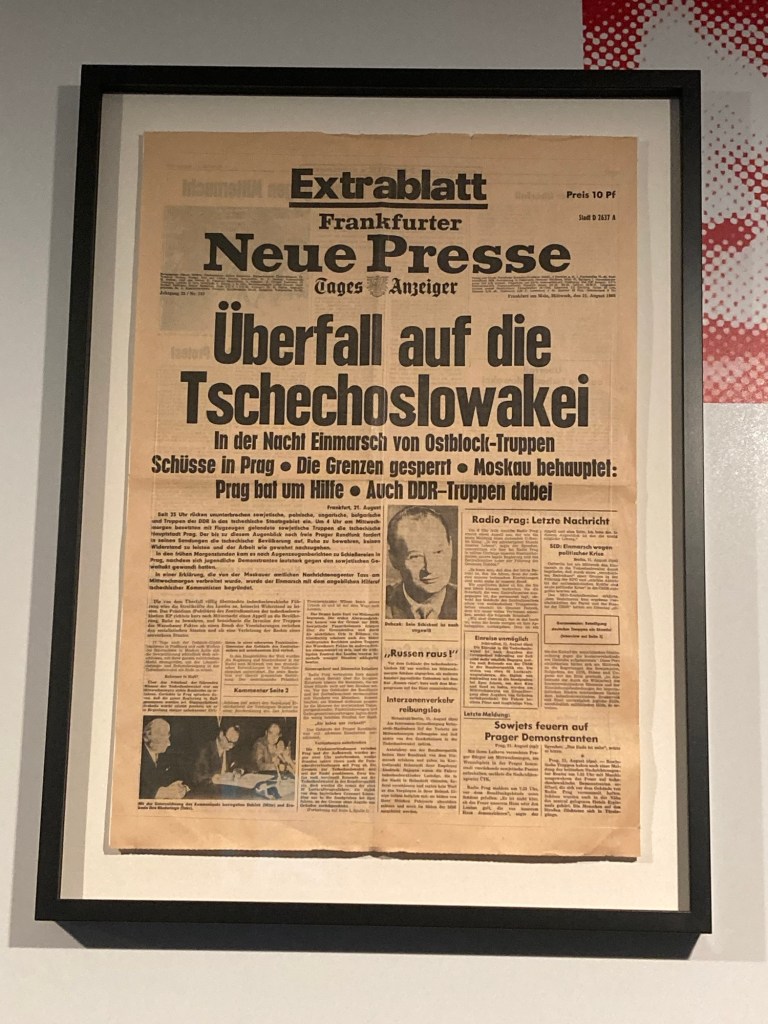

- Prague Spring – Soviet invasion of ‘68 by Warsaw Pact Troops

- Self-immolation by students, artists, and members of the intelligentsia

- Normalisation

- Monopoly on ideology

- Heavy censorship, book bannings and samizdat literature (samizdat means ‘self-publishing’ in Russian)

- Charter 77 by Czech dissidents published in 1977 (a human rights manifesto acknowledging the government had fail to protect human rights in the country)

- Perestroika – a reform programme that didn’t work out (Perestroika means ‘restructuring’ in Russian). This lead to the the downfall of the Soviet Union

- The Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 symbolised the end of the Cold War and the end of communism in Europe

- Velvet Revolution, organised by university students; successfully lead to the end of the Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, and reform; no deaths

“The fall of Communism took 10 years in Poland, 10 months in Hungary, 10 weeks in Germany, and 10 days in Czechoslovakia”.

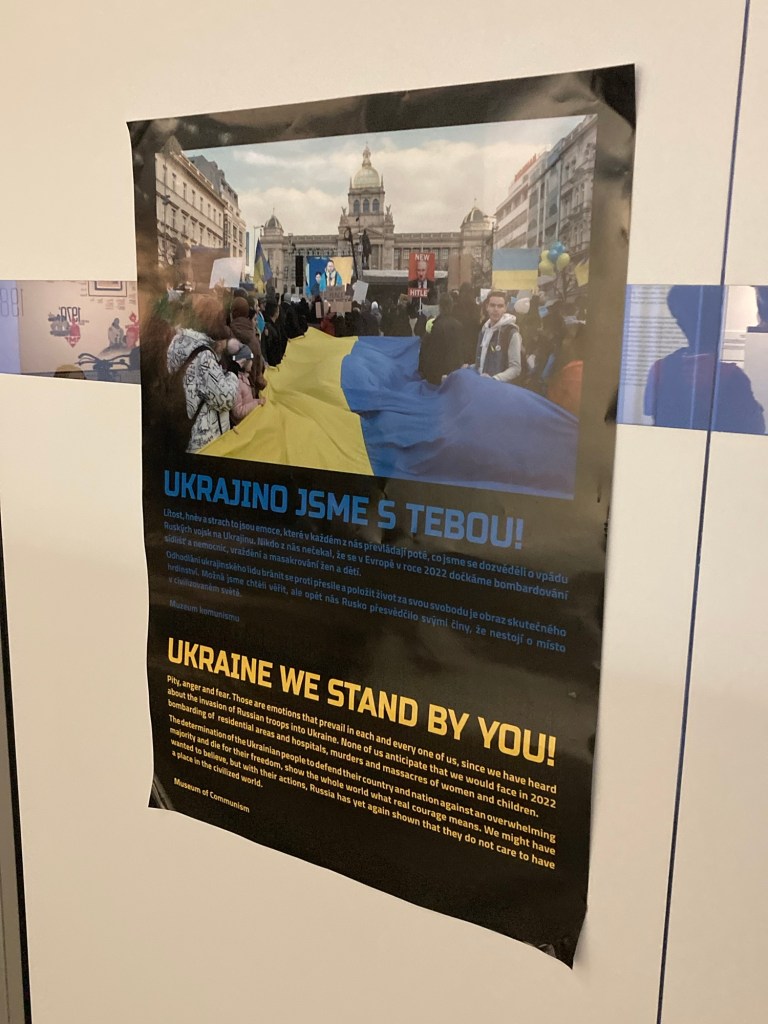

There was a touching poster included at the end, near the exit, about Ukraine.

One thing I observed during this trip is that history is cyclical.

At 18:02, it was 14°C outside and raining. The sun was due to set in 11 minutes. I raced to make it to Charles bridge to watch the sunset.

I made it to the bridge by 18:19.

I could still see remnants of the sun fading away. Then the lights turned on to illuminate Prague Castle.

I left the bridge by 18:42 and walked to a restaurant I wanted to eat at called “Havelská Koruna.” It was about a 10 minute walk from where I was, but fairly straight in one direction.

I arrived at 18:55, where I scavenged their illuminated menu posted outside. There were many options available, and I translated them right then and there on my phone. Six minutes later (yes, six), I had my food.

I ordered bramborové knedlíky plněné uzeným masem 2ks, zelí (potato dumplings filled with smoked meat 2 pieces, cabbage). As well as dukátové buchtičky s vanilkovým krémem (ducat buns with vanilla cream). The term “ducat” refers to a golden European medieval coin that was used for trade. I believe the name is meant to refer to the sweetness or value of the taste. Perhaps their look. Essentially, the buns are named after booty (the pirate type).

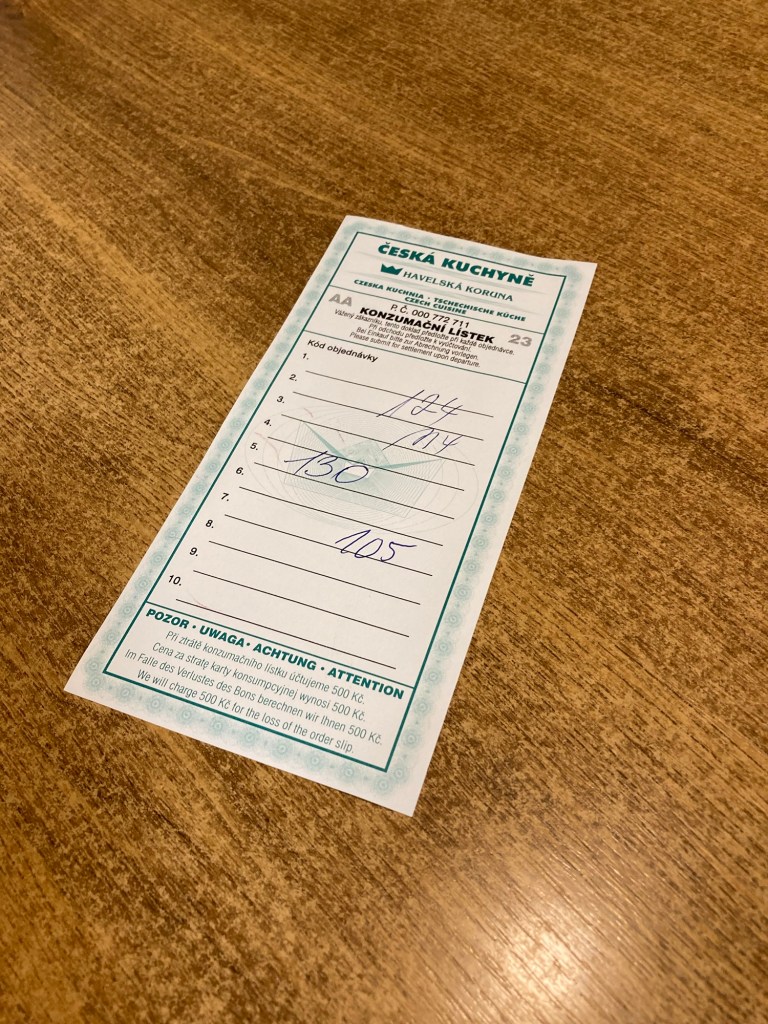

The restaurant works like a cafeteria-style setup. I was handed a blank slip when I went in, and there were different counters I could go to to get food. When I told the people at the counter what it was I wanted, they would ask for the slip and mark it. I received silverware from them as well. There were numbers on the ticket that corresponded with what I had ordered. The food was ready right away; it was hot.

I was really hungry after being in that museum for about four hours.

I chose the seat that was by the window, slightly behind the menu outside, but positioned to where I could still see the action in the street.

There was a painting of Charles Bridge on the wall in front of where I was eating.. Next to that was an interesting little two-weight wall clock, with the weights resembling testicles (one side being lower than the other).

After using the restroom, I left the restaurant at 19:46, fourteen minutes before they shut for the night.

Walking back to my hostel, I came across a tower I had not seen before called, “Vèz Novomèstské radnice” (New townhall tower, in English). This was the site of the first defenestration in Prague in 1419.

I saw another tower as well, this one coming from Saint Stephen’s Church (Kostel svatého Štěpána).

Shortly after, I saw an advertisement for the Museum of Communism. Right next to that was an advertisement for a 50 Cent concert coming to Prague two weeks from the date.

Continuing my walk, I saw two different crosswalk buttons, one older looking than the other.

I made it back to my hostel around 20:30.

Discover more from Jaden Strong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.